Antipode: excerpt 1

Chapter 1: You Are Here

The great Pacific was just a mile from our house when I was a child, and when I needed to be reminded of my own insignificance I would head down to the beach to stare across the vast ocean. In the spring, my father would drive us out of Los Angeles and into the desert, where my brother and I ran through endless fields of erupting wildflowers. The golden-orange California poppies, so garish and delicate, were my favorite. Other than those few weeks each year, when sporadic rain caused flowers to actually grow wild, little grew without tending in L.A. I grew up, daughter of an Iowa farm boy turned computer engineer, believing that things don’t grow unless people make them do so. My mother made our garden grow, carefully doling out water and nutrients, and if she stopped, everything died. Behind, under, between her plants, animals from the hills scurried, reveling in this unexpected bounty. My fierce, loyal cat brought me alligator lizards. She would bite off their tails on my bed, where she would leave the tail, twitching, for me to find. It was a clue that somewhere in my bedroom a lizard with a bloody stump was hiding, terrified. This was our game, hers and mine.

Every fall, scorching Santa Ana winds would come in from the east, pummeling our already parched city. If the winds coincided with a spark in the hills, brush fires erupted, sweeping across chaparral and houses with similar abandon. I remember one fire, coming over the mountains towards our house, now four, maybe five blocks away. I stood on the roof with my father, a little girl, with all the neighborhood fathers on their roofs, hoses in hand, wetting down the tinder of our lives. The fire, which we could not yet see, kissed our faces with raw heat. Finally my father ordered me down, back to the room where my mother had put my little brother and our two cats. We were ready to escape to a car packed with family photos, as soon as my father yelled go.

I fell asleep curled on a pile of blankets. The next morning I woke confused, sweating, my sinuses filled with ash. The winds had turned, and the danger was past. My parents were haunted by our closest call yet, while the children and animals clamored for breakfast.

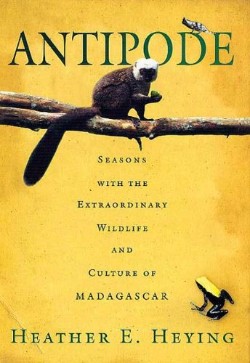

Days later, I walked through those hills while the ground was still hot, chasing lizards and snakes left uncharred. Gone were the scrubby desert plants, the only natives left in L.A. Most gardens remained, though, filled with foreign plants like agapantha and bougainvillea and night-blooming jasmine, and with yet more exotic plants, from places I could only imagine—from Brazil, and from Madagascar. The walls of books that lined our house helped me conjure these faraway places. Many of my favorite memories from childhood are of being curled up alone with a book, hiding from social obligations. I read voraciously, and developed early on a passion for fantasy and science fiction, and later, for classic literature. A well told story was the best escape, and until I could start generating my own adventurous narratives, I immersed myself wholly in those created by others.

Captivated by great literature all of my life, I was frustrated, in college, to find the opinions of literary theorists dictating which stories were valid, and which were not. I left literature for science then, enticed by the promise of distinguishing between plausible and implausible stories through the scientific method. Initiating my turn towards biology was Bret Weinstein, a friend since high school who, in the summer of 1989, handed me a book by the evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, suggesting that I might find some meaning therein. I found The Selfish Gene first daunting, then provocative, and finally inspiring.

Bret has now been my best friend and lover for many years, and his enthusiasm for evolutionary biology contributed to my own desire to be a field biologist. In 1991, before either of us ever saw Madagascar, we backpacked together through Central America, and discovered firsthand the wonder of tropical ecosystems, the sheer pleasure of finding animals in the wild, and being allowed the privilege of watching them do what they do. It’s nothing like being at the zoo and finding the monkeys in their enclosures. When you’re out in their world, in a vibrant, breathing forest, their real lives are arrayed in front of you in all their complexity. Filled with hunger, predators, and treefalls, those lives can change and grow as you watch.

In a way, literature and science are as different as they could be, one seeming to celebrate all the possible alternatives, the other trying to pinpoint which is most likely to be true. But in another way, literature and science are similar, as both aim to construct good stories from real life. Scientific inquiry takes the process a little farther—it takes the possible narratives and assesses if they make sense, puts them to rigorous tests. Students of literature know that blood is thicker than water. Science offers us the opportunity to understand precisely why this is so. In science we rely on hypothesis generation and falsification to assess the validity of our stories. But it’s still stories that we’re generating, and the most interesting stories will always have intrigue and drama, and discovering a story previously untold will forever be exciting.